| Previous

Page |

PCLinuxOS

Magazine |

PCLinuxOS |

Article List |

Disclaimer |

Next Page |

Digital Photography: A Personal History & A FREE Course |

|

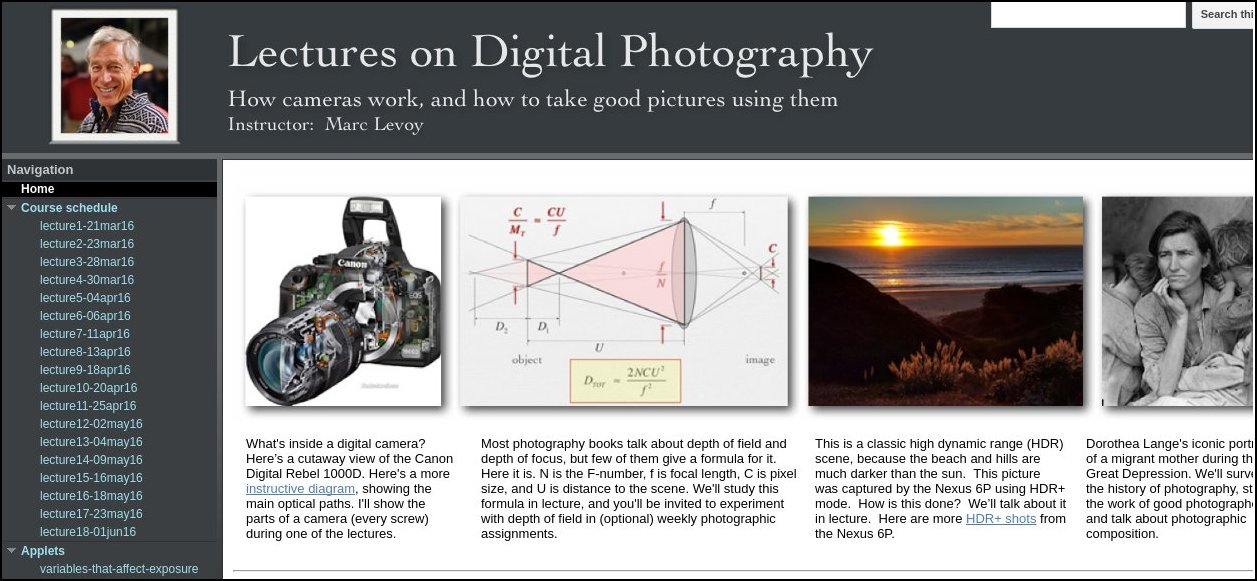

by Paul Arnote (parnote) Back in what seems like another lifetime ago, when I was employed as a newspaper photographer, film ruled the still photography landscape. Quite simply, there was nothing else you could use at that time. But towards the end of my photojournalism career, there was some barely audible thunder on the horizon, as the first viable digital still cameras started to appear for consumer use. Just as with any new technology, it was priced WAY out of reach for the casual user. Heck, it was priced way out of reach for even me, as a working professional photographer. Plus, the digital still cameras that were emerging offered nowhere near the resolution that film provided. I remember the conversation that ensued fairly well. We -- me and all my fellow comrades-in-arms photographers -- took a look at the new "digital" photography stuff and concluded that there was no way that digital still cameras would EVER supplant or replace film, due to film's significant edge and advantage in quality.Boy, were we ever fooled -- and grossly mistaken! What we couldn't foresee at that time was the explosive growth and advancements in the computer industry (processor speeds, RAM, storage, etc.), which partly fueled the explosive growth of digital photography. Development and advancement of camera sensors followed suit, to further hasten digital still photography's rise to prominence. Today, digital photography is the standard, having all but replaced film in most uses.  Even though I still have most of my film based camera equipment, I have also purchased and used no less than seven (7) digital cameras since digital photography emerged from the shadows and marched to the forefront of the still photography landscape. I even still have my first digital still camera: a Sony Mavica FD73 that stored its whopping 0.3 megapixel images on 3½" floppy disks (above left). Since CF memory still ruled the memory card market at that time (and I wasn't a fan), I "graduated" to a Sony CD Mavica 300 (above right), which stores its images on mini CDs placed in the back of the camera. It also allowed me to increase my resolution 11 times, to 3.3 megapixels! Today, I have a variety of digital still cameras -- including the two listed above. Plus, this doesn't count the fairly decent quality digital still camera built into my cell phone. I have a couple of small, pocket model digital still cameras that I can shove into a pocket if I think I might need something when I'm casually out and about (or when I go hunting and fishing). I have a couple of other larger cameras that I call "near dSLR" (some call them "super zoom" cameras). They are styled like a dSLR, but lack the ability of changing lenses. Then, I have my dSLR (digital single lens reflex) camera. Here is my current "inventory" of dedicated digital still cameras:

I prefer cameras that use common, off-the-shelf batteries (AA or AAA). That way, when I am "out and about" and my batteries die or get low, replacement batteries are always near and available. With the exception of the first two cameras listed above (which are pretty much in retirement), my Casio compact pocket camera (semi-retired), and my Canon dSLR, all of my other cameras use common AA batteries. I typically use rechargeable NiMH or lithium ion batteries, and usually carry a couple of sets with me when I take/use those cameras. However, the ability to buy a set of alkaline batteries at the local drug store, convenience store, gas station, or just about any other location has really saved my bacon several times, and allowed me to continue capturing the photos I wanted and needed.  Both the Canon and Fujifilm cameras above use AA batteries, which could be important if you travel with your camera a lot. You can find cameras that use AA batteries here. One camera that keeps popping up on that list that looks particularly appealing is the Nikon B500 with its 40x optical zoom lens and 16 MP image resolution. Although it has a suggested retail price of $300 (U.S.), you can get the camera new for right around $250 (U.S.). I add this bit for those who may be interested in getting a quality super zoom digital still camera, without the expense and complicated operation of a dSLR, that's capable of delivering high quality images. It is definitely one model I would choose (if I were in the market for another super zoom digital zoom camera). Another model to look at would be the Fujifilm Fine Pix S1, which sells for around $350 (U.S.). Being locked into a proprietary battery system has advantages, like rechargeable, longer lasting lithium ion batteries, but there are also drawbacks. Their use requires you to plan ahead (making sure your primary battery is fully charged), have extra charged batteries available (which have to be purchased for an additional cost, and then make sure they are charged), and possibly purchase additional accessories, like battery chargers that work both in the car and when plugged into an electrical outlet. If you're a gadget freak ("Hello. My name is Paul, and I'm a gadget freak."), then the latter probably isn't going to be much of an issue, since you're going to be buying all sorts of additional accessories anyways. I have noticed the pendulum swing back and forth a couple of times in the short history of digital still cameras on the preference of manufacturers to use either proprietary battery systems or common, off-the-shelf batteries. Without a doubt, the use of proprietary battery systems means more profits for the manufacturers, since you'll most likely buy them from the camera's manufacturer. But, in a similar vein, use of common, off-the-shelf batteries means greater convenience to the end user. Currently, the pendulum seems to have swung back in favor of proprietary battery systems.  The Nikon and Casio pocket cameras offer point and shoot capabilities, as well as being small enough to fit into a shirt or pants pocket (the latter is not recommended, however). An added bonus is that their size makes them very unobtrusive, and many people won't even realize that you're taking pictures. Typically, when you go with the smaller, point and shoot pocket cameras, you don't have a lot of control over the camera's settings. Those cameras do a pretty fair job of getting you a decent picture. You get a bit more control over the camera's settings when you move up to the super zoom cameras. At the other end of the spectrum are the dSLR cameras, where you typically have total control over the camera's settings, plus a variety of "automatic" modes to choose from. LOTS of similarities When I switched careers from photojournalism to working in healthcare, I had reached the all-too-common burnout point for photojournalism. The stress and low pay definitely took its toll. Plus, it's really difficult to get your hands on the latest and greatest equipment when the pay is so low. In a way, I'm glad to have switched careers when I did, because the switch from film to digital came along a few years later. Don't get me wrong; I loved photography then, and I love it now. I taught myself photography when I was 12 years old. For as long as I can remember, it's what I really wanted to do -- and I consider myself fortunate to have done it. But, there's no way I could have afforded the pro level digital gear that would have been necessary to keep me competitive and employed. That burnout had actually made me shun photography for a period of time after leaving the profession. It was the emergence of digital photography that reignited my love for photography. No longer did I have to pay to have my photos processed. No longer did I have to do the processing myself, either. Now, all of my images could be accessed on my computer, my "new" interest. The marriage of the two created a perfect storm to help me rediscover the love of photography that I possessed in my teenage years. Forty years later, I have as much enjoyment using software to tweak my photos as I did by doing so in the darkroom. The software has become my darkroom. Regardless of the storage medium -- film or digital files -- the truth of the matter is that the basics of photography still rule supreme. The basics for good image composition apply (rule of thirds), without regard to the storage medium. Depth of field is still depth of field. Focal length is still focal length. The same caveats about using high ISO ratings with film still apply to ISO settings in the digital realm. Fast shutter speeds still freeze action. Slow shutter speeds can still blur faster moving objects. So, if you are moving from film to digital, all of the photography basics remain the same. Thus, all of your skills and knowledge are easily transferred to this newer medium. Knock off the rust, gain new skills Thankfully, there is a FREE digital photography course out there, presented by one of the pioneers in digital photography, Dr. Marc Levoy, Ph. D. He is professor emeritus at Stanford University, where he taught a course on digital photography from 2009 to 2014. He subsequently retired from Stanford University, and now leads a team in Google Research. In 2016, he revised the digital photography course he taught at Stanford, and taught it at Google. The 18 lectures were recorded live, and they have now been made available online, completely free.  You can access Levoy's digital photo course here. They have proven to be very popular since their release, and some users have reported problems accessing the lectures. On September 7, 2016, the following statement appeared on the site: Update on September 7, 2016: this course seems to be popular, causing Google Drive to temporarily refuse to serve some of the lecture videos. If you get an error message that says, "Unable to play video at this time" when you click on Play for a lecture, you can instead access the video on my YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/marclevoy/videos. Here is a playlist of all 18 lectures, in order: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL7ddpXYvFXspUN0N-gObF1GXoCA-DA-7i That said, some of the videos have been flagged by YouTube as violating copyright and even blocked in some countries. The problem is that YouTube doesn't know these are lectures, which ought to fall under "fair use". I have edited the YouTube version of lecture #5 to remove copyrighted content that was blocking it in many countries, and re-uploaded that lecture to YouTube. If you can't find other lectures on YouTube in your country, come back here and wait for Google Drive to resume serving that video.Levoy's website also contains interactive, web based "applets" that help to further explain and demonstrate some of the various concepts in photography. He also includes examples of bad photos, as well as some of the best photos taken by the participants/students in the course. All of these are still accessible on his website, even if the lecture videos may not be. So, you may need to access the videos on YouTube, and access the web applets in another open tab in your browser. Summary Make no mistake about it, photography has undergone some dynamic and formidable changes in the last 25 years. Digital photography has largely replaced film as the ruler of the kingdom. Despite the replacement of film by electrons, however, the basics of photography have not changed, and I doubt that any of that will ever change. Plus, if the rest of Marc Levoy's lectures are as interesting as the bits and pieces I previewed to write this article, they represent a very real royal treasure to photographers all around the world, from all walks, regardless of their backgrounds. His lectures offer something for both beginning and seasoned photographers alike. While some of the topics may seem a bit overwhelming to beginning photographers, he presents the information in a very clear manner that's easy to digest. For example, you do not have to know the formula for depth of field to be a good photographer. Levoy's lecture was the very first time I ever heard of or saw this formula, and I've been a photographer for all of my life. However, to be a good photographer, it does help to understand the concept of depth of field and how it works, along with all the other topics that Levoy covers. |