| Previous

Page |

PCLinuxOS

Magazine |

PCLinuxOS |

Article List |

Disclaimer |

Next Page |

March 14th: A Geek's Perfect Holiday? |

|

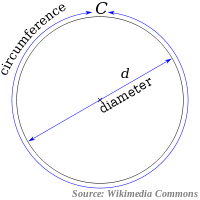

by Paul Arnote (parnote) Geek. Nerd. Dweeb. Dork. Use whatever name you wish, but March 14 is a day of celebration for many intellectuals. π Day First, that day -- 3.14 -- is the first three significant digits of the mathematical expression more commonly known as π, or pi. The first large scale, organize Pi Day was in 1988, by physicist Larry Shaw when he worked at the San Francisco Exploratorium. Staff and public visitors marched around one of the Exploratorium's circular spaces, consuming fruit pies. In 2009, a non-binding resolution was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives, recognizing March 14 as "National Pi Day."Over the years, the celebration of Pi Day has taken on various celebratory themes. Those include pie throwing, pie eating, discussing the significance of pi, and holding contests to see who can recall pi to the most number of decimal places. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has been known to mail application decision letters to prospective students so that the recipient receives them on March 14. Here's how Wikipedia sums up pi: The number π is a mathematical constant that is the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter and is approximately equal to 3.141592654. It has been represented by the Greek letter "π" since the mid-18th century, though it is also sometimes spelled out as "pi" (/paI/). Being an irrational number, π cannot be expressed exactly as a common fraction. Consequently, its decimal representation never ends and never settles into a permanent repeating pattern. The digits appear to be randomly distributed, although no proof of this has yet been discovered. Also, π is a transcendental number -- a number that is not the root of any nonzero polynomial having rational coefficients. The transcendence of π implies that it is impossible to solve the ancient challenge of squaring the circle with a compass and straight-edge. Fractions such as 22/7 and other rational numbers are commonly used to approximate π. For thousands of years, mathematicians have attempted to extend their understanding of π, sometimes by computing its value to a high degree of accuracy. Before the 15th century, mathematicians such as Archimedes and Liu Hui used geometrical techniques, based on polygons, to estimate the value of π. Starting around the 15th century, new algorithms based on infinite series revolutionized the computation of π. In the 20th and 21st centuries, mathematicians and computer scientists discovered new approaches that -- when combined with increasing computational power -- extended the decimal representation of π to, as of late 2011, over 10 trillion (1013) digits.[1] Scientific applications generally require no more than 40 digits of π, so the primary motivation for these computations is the human desire to break records, but the extensive calculations involved have been used to test supercomputers and high-precision multiplication algorithms. Because its definition relates to the circle, π is found in many formulae in trigonometry and geometry, especially those concerning circles, ellipses, or spheres. It is also found in formulae from other branches of science, such as cosmology, number theory, statistics, fractals, thermodynamics, mechanics, and electromagnetism. The ubiquitous nature of πmakes it one of the most widely known mathematical constants, both inside and outside the scientific community: Several books devoted to it have been published, the number is celebrated on Pi Day, and record-setting calculations of the digits of π often result in news headlines. Attempts to memorize the value of π with increasing precision have led to records of over 67,000 digits. π is commonly defined as the ratio of a circle's circumference C to its diameter d.   The ratio C/d is constant, regardless of the circle's size. For example, if a circle has twice the diameter of another circle it will also have twice the circumference, preserving the ratio C/d. This definition of π implicitly makes use of flat (Euclidean) geometry; although the notion of a circle can be extended to any curved (non-Euclidean) geometry, these new circles will no longer satisfy the formula π = C/d. There are also other definitions of π that do not mention circles at all. For example, π is twice the smallest positive x for which cos(x) equals 0. Albert Einstein's Birthday Is it any wonder that March 14 is the birthday of the greatest physicist ever known to mankind, Albert Einstein (1879 -- 1955)? In fact, some have tried to make some great cosmic connection out of Einstein's birthday being on the same day as the first three significant digits of pi.  Einstein is best known for his theory of relativity. His works are still a guiding force in modern day physics. Born in Ulm, Germany, he emigrated to the United States in 1933 to escape the persecution of those born with Jewish heritage by the Nazis. By 1935, he decided to stay permanently, and became a U.S. citizen in 1940. Undisputedly, he is very well known. He is one of the best known scientists to have ever lived, if not the best known ... period. Many books have been written about him. "Einstein" has even become a synonym for genius. Below are some -- a baker's dozen, to be precise -- interesting facts you might not have known about him, though. Albert Einstein played the violin. Albert became passionate about the violin after hearing Mozart. In fact, his favorite piece was Mozart's Sonata in E Minor. Albert would play the violin whenever he got "stuck" in his thinking process. He was also known to play privately for friends, and would join in with his violin when Christmas carolers came to his door. He even named his violin "Lina." Albert Einstein hated socks. In fact, he rarely (if ever) wore them. He didn't like them, because they were always getting holes in them. He also figured why wear socks and shoes, when only one will do. Albert Einstein loved sailing. Back when he lived in Germany, Albert owned a boat. But on a trip back from the U.S., he found out that his cottage and boat in Germany had been confiscated by the Nazis. Once back in the U.S., Albert pursued his love of sailing. He would often take a sailboat out on days with very little wind, relishing the challenge of capturing even the smallest amounts of power that was available. Albert Einstein had an illegitimate daughter. Although not much is known about her, letters from Albert refer to her as Lieserl, a shortened name for Elisabeth. She was born in 1902, and either was either put up for adoption, or died of scarlet fever during infancy. Her real name and fate are unknown, and it is suspected that Albert never saw his daughter. Albert Einstein was married -- twice. With his first wife, Mileva Marić, Albert not only had his illegitimate daughter, but he also had two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard. Married in January 1903, they divorced in February 1919, after having lived five years apart. His second wife, Elsa Lowenthal, was also his first cousin on his mother's side and his second cousin on his father's side. They were married in 1919, and Elsa emigrated to the U.S. with Albert in 1933. However, she died in 1936 after experiencing heart and kidney problems. Albert Einstein has five surviving great-grandchildren. Eduard, nicknamed TeTe by Albert, never had children, suffered from schizophrenia and spent parts of his life in an asylum. Hans Albert, however, had a son named Bernhard Caesar Einstein. Bernhard had five children, who are all surviving. They live in California, France and Sweden. Despite the fame associated with the family name, the Einstein family is in shambles. Albert Einstein didn't talk until he was four years old. Afraid that their son was "retarded," Albert's parents' fears were put to rest when he broke his silence at the dinner table one evening. He uttered the words, "the soup is too hot," according to all accounts. When his parents asked why he hadn't said anything until now, Albert is reported to have replied, "because up until now, everything was in order."

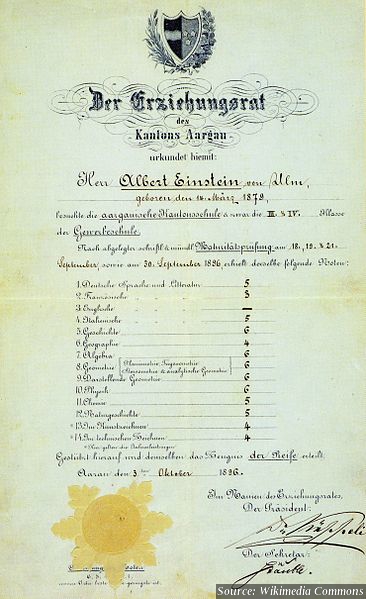

Albert Einstein was not a straight "A" student. Despite his very high intellect, Albert was not a straight "A" student. In fact, he failed his first college entrance exam and had to go to a trade school for a year before reapplying for admission to the university. At the trade school, Albert got pretty good grades (above), and attended Zurich Polytechnic the following year with a major in mathematics and physics. Albert Einstein was a pacifist. But he wasn't blind about it. In 1939, a group of Hungarian scientists attempted to warn Washington, D.C. politicians and policy makers about Germany's attempts to build an atomic bomb. Their warnings were dismissed and not taken seriously. One of the group's members urged Albert to lend his name and credibility to the cause, and Albert signed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It warned him of the German atomic research, including the possibility of developing an atomic bomb, and urged Roosevelt to do likewise. As a result, the U.S. was the only country during World War II to develop an atomic bomb before the end of the war. We now know that Hitler and the Nazis weren't far behind, either. In 1954, a year before his death, Einstein said to his old friend, Linus Pauling, "I made one great mistake in my life -- when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification -- the danger that the Germans would make them ..." Albert Einstein may have hastened his own demise. Albert died on April 18, 1955. He had a second abdominal aortic aneurysm (he had one previously treated, surgically). The doctors suggested surgery, but Albert refused and replied, "I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly." Albert Einstein was a member of the NAACP. Even before Albert emigrated to the U.S. in 1933, he corresponded with W. E. B. Du Bois, one of the founders of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). He campaigned for the civil rights of African Americans. In 1946, Albert called racism America's "worst disease." He later added, "Race prejudice has unfortunately become an American tradition which is uncritically handed down from one generation to the next. The only remedies are enlightenment and education." Albert Einstein had a bad memory. Albert could not remember dates and phone numbers. In fact, he didn't even know his own phone number. It all started with a compass. Albert's fascination with science is rooted in a simple compass. When Albert was five years old and laying sick in bed, his father showed him a simple compass. He wondered about what force exerted itself on that tiny needle to make it always point in the same direction. That question would haunt Albert for many years, providing the catalyst for his scientific curiosity that would blossom and last a lifetime. Summary Well ... it's probably way more than you wanted to know about π Day or Albert Einstein, but now you can see why March 14 is such a glorious day for geeks everywhere. |