| Previous

Page |

PCLinuxOS

Magazine |

PCLinuxOS |

Article List |

Disclaimer |

Next Page |

Firefox & DRM: Anything To Worry About? |

|

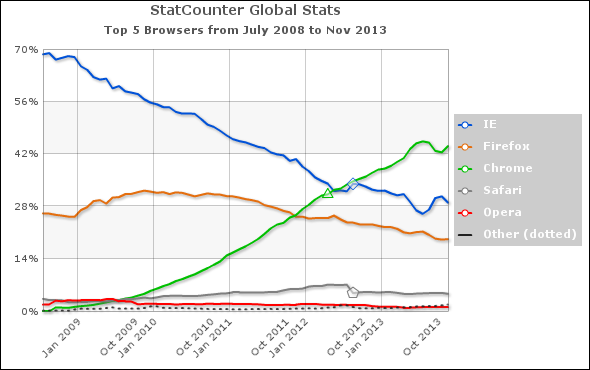

by Paul Arnote (parnote) In the middle of May, Mozilla announced to the world that they will embrace a new DRM (digital rights management, or digital restrictions management, as Richard Stallman has called it) scheme for the playback of protected (some might say restricted) content. That scheme, called EME (encrypted media extensions), will utilize a CDM (content decryption module) to stream protected content through the user's web browser. As you might imagine, the initial uproar among the web community was loud and quite negative. Our beloved open source browser would now include closed source DRM modules. Or, is it really as the nay sayers and negative Nellies initially think? Let's try to step back and look at this issue with a wider perspective. As early as January 2013, talk was circulating about the W3C consideration to include DRM specifications in the HTML 5.1 specifications. On September 30, 2013, Sir Tim Berners-Lee and the rest of the W3C committee signed off on such a DRM specification, called EME. This proposal was from Microsoft, Google and Netflix, and was put forth to try to standardize DRM. Mozilla, the makers of Firefox, fought the proposal at every step along the way. Mozilla put up one helluva good fight. But at the end of the day, all of their fight was for naught. They were outmanned, outmaneuvered and outvoted. Consider, if you will, the environment surrounding Mozilla's decision. Opera, IE and Chrome all support the EME/CDM specifications. That left Firefox as the only major browser vendor not supporting the DRM specifications.  Browser market share, July 2008 to October 2013 (Source: browsermarketshare.com) As popular as Firefox is, especially among Linux users, Firefox's share of the browser "market" has been declining over the past five years. In that same time span, Google's Chrome browser has come from virtually no market share to becoming the predominant browser in the browser market. The LAST thing Mozilla developers want is for users to have to use another browser to view protected streaming content. But unless Firefox supported the EME/CDM DRM specifications, users would be forced into doing just that. The risk of losing those users altogether becomes significant, as those users may just opt to use that "other" browser as their predominant browser. DRM: A Double Edged Sword Indeed, DRM really is a double edged sword. On one hand, content providers want a way to protect copyrighted material from being pirated. You can hardly blame them. On the other hand, DRM, as it currently exists, is extremely burdensome on the end user. The user must have the right "keys" (extensions, plugins, etc.) to unlock the content. It's also frequently not very easy to stream the same content on multiple devices. In many cases, if you "purchase" the keys to view protected content on one device, you often cannot view it on another device. Instead, you have to "buy" another key on the other device. That situation is a bit akin to buying a DVD, restricting the playback to just ONE DVD player, then having to buy another copy for every DVD player you want to play it back on. Generally speaking, the current DRM situation doesn't allow for "fair use," preventing playback of the purchased copy of the protected content on more than one device. Mozilla's preference was for watermarking content with something that uniquely identified the user. This would allow for the same content to be used between all the different devices a user might possess (smartphone, tablet, computer, desktop device, etc.), but provide a barrier to illegal file sharing. Should a user choose to share a file, the watermark would lead authorities back to the origin of the pirated copy. Many have argued, rightfully so, that DRM is just a way for content providers to hang on to old business models, and avoid adapting to changing markets and market conditions. As it is in its current form, DRM heavily favors content providers and creates a nightmare for end users trying to jump through all the DRM hoops. In many ways, DRM encourages piracy of protected content, as users will try to circumvent DRM, rather than paying three times for streaming the same content on multiple devices, regardless of the existence of any laws (such as the Digital Millenium Copyright Act). Plus, there are those users who just love the challenge of trying to defeat any DRM, and they post their "successes" to share with everyone else. So what does all of this mean? Not much, if you stop and think about it. DRM already exists, in one fashion or another, through Silverlight (although not on the Linux platform) and Adobe Flash content. You already watch Flash content, and many Linux users are hell bent on trying to view Silverlight protected content under Linux. According to Mozilla, you will always have the ability to say NO to installing the DRM modules, just as you can currently do with Flash or any other plugin module. No one is forcing Firefox users into accepting DRM. That ability will, true to Mozilla's stated goals, remain with the end user to decide to accept -- or not. The good thing about the EME/CDM DRM scheme is that it spells the end to Silverlight and Flash -- eventually. Those two atrocities have needed to go away a LONG time ago, and their departure cannot happen fast enough. Instead, users will have one "standardized" DRM scheme to deal with that should work across all platforms. You can read more about Mozilla's decision to reluctantly enable DRM in Firefox here and here. Users shouldn't blame Mozilla. After all, they are simply wanting to maintain their current market share, and perhaps even increase it. If anything, users should place blame equally on content providers tenaciously holding onto their old business models, and on the W3C -- Sir Tim Berners-Lee included -- for capitulating to the whiny demands of those content providers. Like it or not, DRM content is here to stay -- at least for the time being. And it will remain that way until content providers embrace the digital age and adapt to the new business model that it brings with it. Currently, content providers want to embrace the digital age, but wrap it up in their old, outdated business model. Until that changes, DRM will be an ever present scourge upon content consumers. |