| Previous

Page |

PCLinuxOS

Magazine |

PCLinuxOS |

Article List |

Disclaimer |

Next Page |

Repo Review: Zim |

|

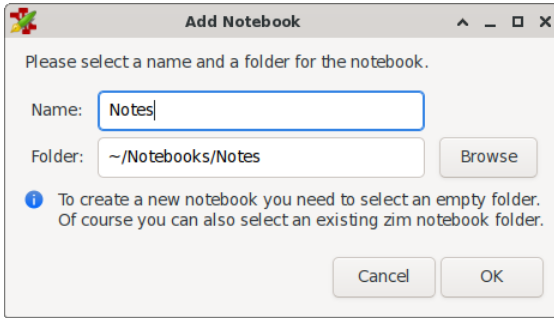

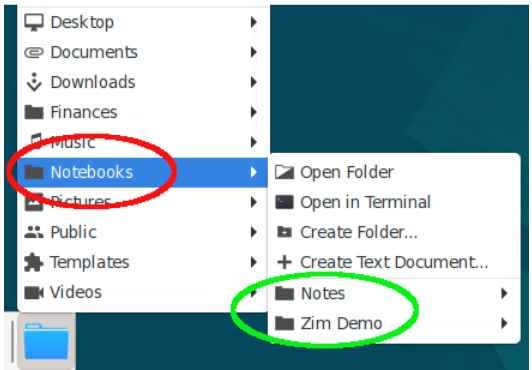

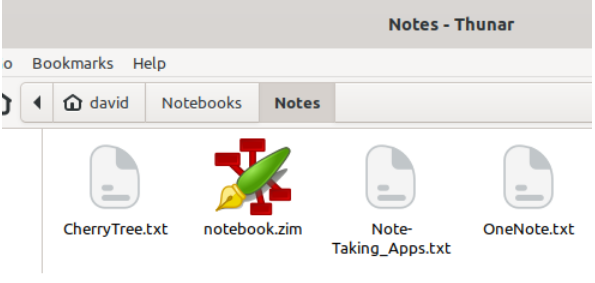

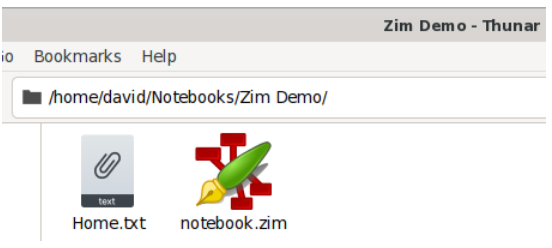

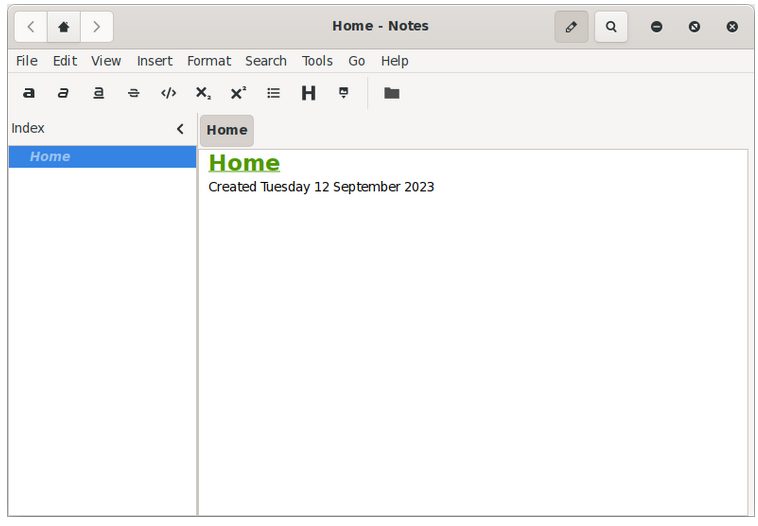

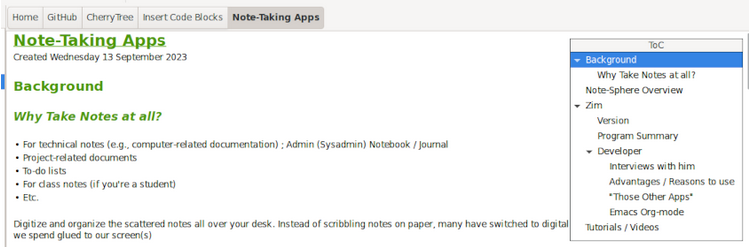

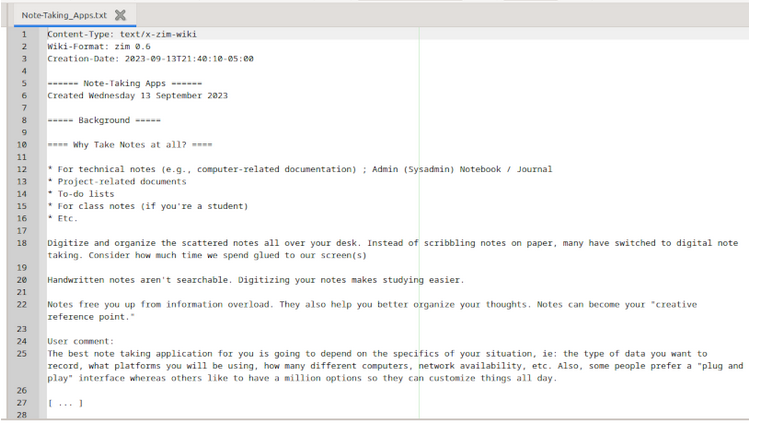

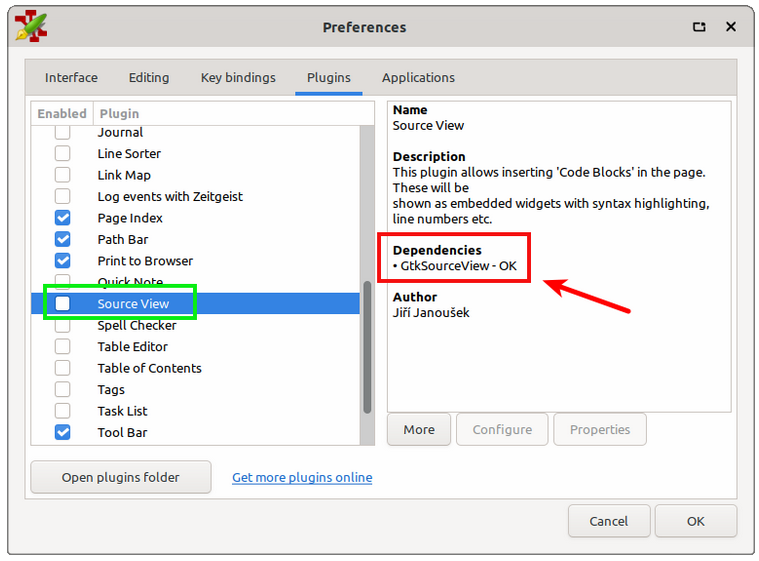

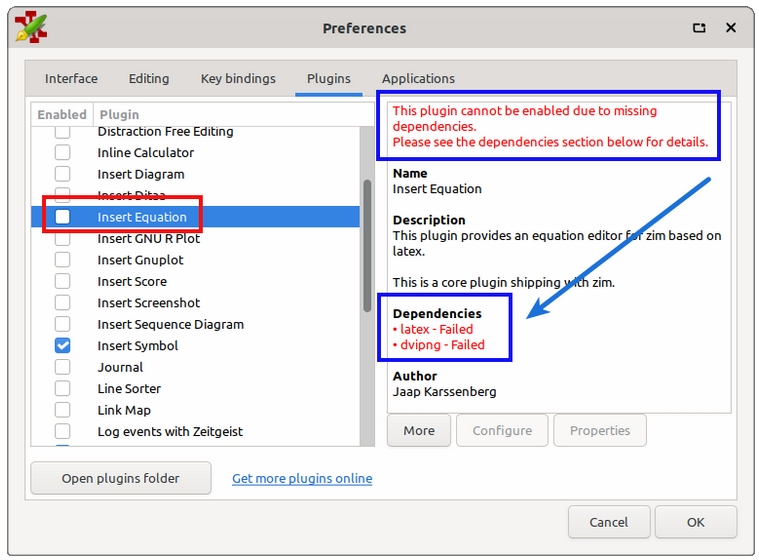

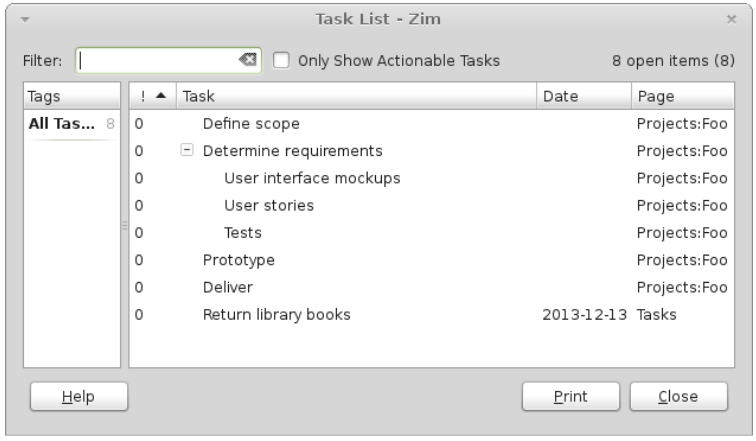

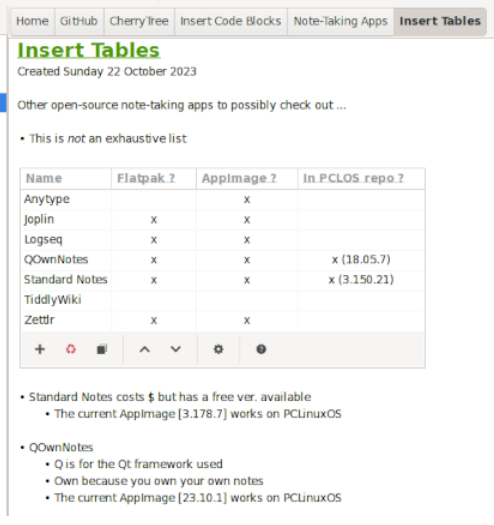

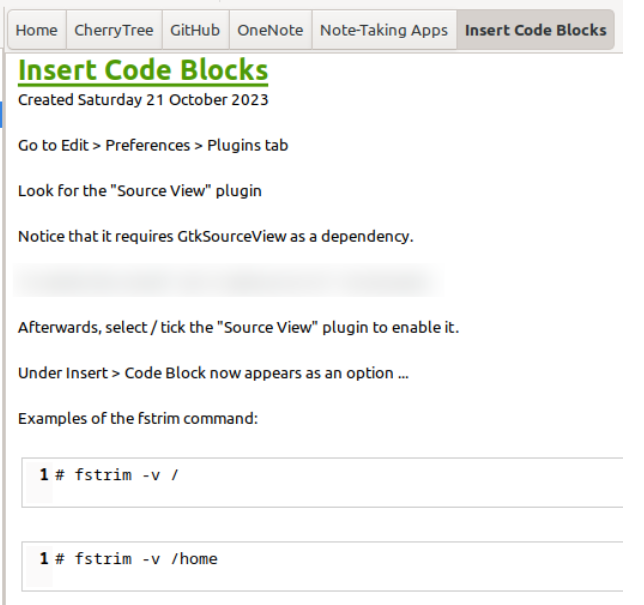

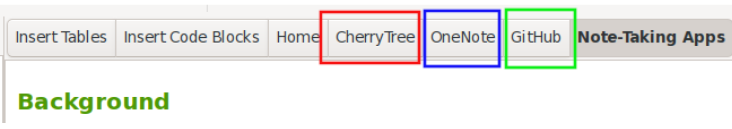

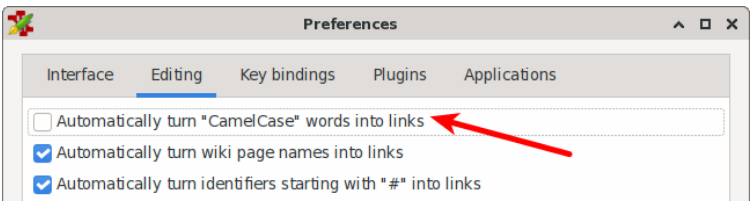

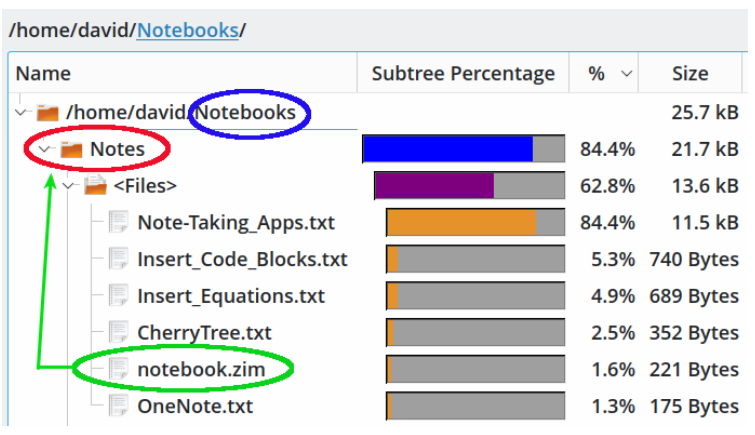

by David Pardue (kalwisti) When I prepare an article for our community magazine, I follow an old-school approach; I gather information from an assortment of online sources, taking notes with pen and paper. Then I try to organize my notebook sheets in a logical way before creating an outline and typing my rough draft in a word processor. As an experiment, I have begun to explore the world of digital note-taking to see if it might be more efficient and flexible for my workflow. The Growth in Note-Taking Apps My search took me down the rabbit hole. In the past few years, there has been a veritable explosion in the note-taking industry. The note-taking tools market is projected to reach a value of $1.35 billion by 2026. A multitude of applications are available. Most of them are commercial, peddle the usual monthly subscription model, and want to lock users into the vendor's ecosystem for the longest time possible. In addition, there can be concerns with the privacy and reliability/data loss of proprietary apps. For an overview and comparison - by no means exhaustive - see the "Encyclopedia of Note Taking Apps" (https://noteapps.info/). Its dataset currently covers thirty-five apps, only five of which are open-source. Zim is not listed but it is under consideration to be added to the website. One factor spurring growth in the digital note-taking space is the concept of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM). PKM is a structured system to organize your thoughts, notes and files. A popular methodology of PKM is called the Second Brain (also known as Building a Second Brain [BASB]). Second Brain is a marketing term which describes a method of organizing your digital life and supposedly unlocking your creative potential. This concept has been developed by Tiago Forte, a guru of digital organization. Forte's book, Building a Second Brain (Profile Books, 2023), describes this methodology. He also offers a pricey online BASB course. From a historical perspective, one of the oldest examples of PKM is the commonplace book. Commonplace books originated in ancient Greece and Rome as a way to compile knowledge, a tool to record and digest information. A commonplace book resembles a scrapbook filled with many different items: quotes, notes, proverbs, aphorisms, poems, observations, etc. Entries are often arranged by subject and category. Famous examples of commonplace books include Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, which began as a private collection of notes and quotations, Erasmus of Rotterdam's rhetoric textbook De copia (1512), and philosopher John Locke's book A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books (1676). Commonplacing was adopted by a variety of intellectuals; Thomas Jefferson kept a commonplace book, and authors like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mark Twain and Virginia Woolf used this technique. In Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories, Holmes keeps numerous commonplace books which he sometimes uses for his research. When discussing PKM, it is easy to get carried away with an elusive search for the "ultimate" note-taking app and system, with the most features and customization. However, we should remember that PKM is just an aid to our work, not the work itself. Note-taking apps do not magically make us smarter; as researcher Andy Matuschak observes, "The goal is not to take notes - the goal is to think effectively." Why Use Zim? Based on my reading, I decided to try Zim because it met my desired criteria: a FOSS program; stable and reliable; my data remains local; files are stored in plain text format; and notes are saved using a standard file and folder structure (rather than being stuck in some proprietary database). Zim is a mature project with an eighteen-year track record, first released in 2005. Zim's developer is Jaap Karssenberg, who works as a System Engineer at ASML (a semiconductor company). He holds a Master of Science in applied physics (2006) as well as a B.A. in philosophy (2007). Karssenberg became involved with the open-source community while he was a university student. His first programming language was Perl. He uses Zim daily for his projects, so he has an incentive to actively maintain it. I found two brief interviews with J. Karssenberg. The earliest one is bilingual (Spanish-English) from October 2008: "Entrevista Jaap Karssenberg, el desarrollador de Zim" (https://tinyurl.com/5af6snbb). The Ubuntu Weekly Newsletter (155 [Aug. 9 - 15, 2009]) also published a brief article, "Zim and the Art of Wiki Development": https://tinyurl.com/8ee9u7xv A Quick Overview of Zim Zim is cross-platform: Linux, Windows 10, macOS (High Sierra [10.13] to Monterey [12]). It is a graphical text editor used to maintain a collection of wiki pages. Wiki is the Hawaiian word for 'quick' (pronounced "we-key" rather than "wick-ee"). Wikis were inspired in part by Apple's HyperCard; the first public wiki was created by programmer Ward Cunningham in 1995. Another way to describe Zim is as a note-taking tool designed to help you maintain a collection of notes in the form of personal wiki pages. In other words, you can have many notes and link them to each other in meaningful ways. Wikis are very useful for storing information (e.g., thoughts, to-do lists, a journal, recipes, interesting quotes, a sysadmin notebook) and building a knowledge base. Another advantage of wikis is that they have little inherent structure, thus allowing structure to emerge according to your needs. When you first start Zim, it asks you to specify a folder for your notebooks and the name of a notebook. I accepted the app's default suggestions (although you may change them if you wish):  "Notebooks" in Zim's terminology are just folders that contain Zim pages, attachments, and folders with more Zim pages. Zim's design decision of creating a folder structure to match the notes structure ensures that even if Zim disappears, my structure will still exist, with my attachments in context to the notes. All my notes do not end up in one large, jumbled folder. The screenshots below illustrate this principle. Within my Zim Notebooks folder, there are two subfolders: Notes and a temporary / test folder named Zim Demo:  The Notes folder contains three Zim pages (with their data stored in plain text files):  The Zim Demo folder contains only one Zim page:  On its first run, Zim's UI looks a bit sparse. There are a few items in the toolbar; the left panel displays your file structure. In the main window (on the right side), you have a standard text editor:  Despite its basic appearance, Zim is powerful and comes with an assortment of plugins that expand its capabilities (accessed via the Edit menu > Preferences > Plugins tab). For example, there is a useful Table of Contents plugin:  The Table of Contents has hyperlinks to the sections / subsections of the page, and clicking on its header bar will collapse it. (In case you are curious, this screenshot shows the underlying text format of the Zim page pictured above:  Some plugins require installing dependencies; Zim will indicate whether the additional packages are present on your system:   Other helpful plugins include a Task List, a Table Editor and one called Source View (which allows you to insert code blocks in the page):    Although I do not have space for screenshots of them all, approximately twenty-five other plugins are available. Worthy of mention are the Spell Checker, Insert Screenshot and Insert Equation (which requires you to use LaTeX markup for equations). If you are not familiar with LaTeX, you can use Yassine Lagrida's "Online LaTeX Equation Editor" http://latexeditor.lagrida.com/) which is free and does not require installing anything; it uses your web browser, a visual editor and JavaScript to generate LaTeX markup for math formulas / equations. Each Zim page can contain links to other pages within the project, URLs, simple text formatting, and embedded images. Another handy feature is the ability to export your notes in HTML format to publish them as web pages. (In fact, Zim's website was written in Zim.) I would like to mention one Zim setting which confused me at first because I did not know the term "CamelCase words." Camel case means writing phrases without spaces or punctuation and with capitalized words. Common examples include "YouTube", "iPhone" and "eBay". In some wiki markup languages, camel case is used for terms that should be automatically linked to other wiki pages. Zim follows this behavior by default; words in camel case have links created on the fly as you type them (results highlighted below):  If you want to disable this behavior, go to the Edit menu > Preferences > then click on the Editing tab to bring it forward. Look for the option Automatically turn "CamelCase" words into links and uncheck / deselect it:  A possible drawback for some users is that Zim does not offer a one-stop mobile solution for note storage, since it lacks a native client for Android and iOS (i.e., for smartphones and/or tablets). However, if you wish, your Zim data can be synced to cloud storage services such as Dropbox, Google Drive or Microsoft OneDrive. You will probably want to work with your Zim notebooks across more than one computer. If so, it is very simple to copy - or back up - your Zim data. All content is located in ~/Notebooks, so just copy the top-level folder of the Notebook (i.e., the one with the notebook.zim file in it) and transfer it to your other PC. On my system which uses Zim's default settings, the relevant folder is named Notes.  Additional Resources These two web-based tutorials provide a good starting point for learning more about Zim: The Zim User Manual: https://zim-wiki.org/manual/Start.html Kidwell, Brendan. "Getting Work Done in Zim." 4 Dec. 2013. https://www.glump.net/content/getting-work-done-in-zim/getting-work-done-in-zim.html If you prefer video presentations, the clearest tutorials I found are below: Done on Linux. "Zim Done on Linux." YouTube, 28 Feb. 2021. (21 min., 59 sec.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJVmLF_Z7qQ Pandora's way. "Zim: Ultimate Note Taking Guide in 26 Minutes." YouTube, 6 May 2022. (26 min., 17 sec.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qa5wa7AmvRE Summary Zim is an impressive tool if you need to take organized notes and like wiki-style documenting. It is a real desktop app that is reliable, fast, consumes minimal resources and is ready to use out of the box. Your notes stay on your own computer, under your control rather than being "siloed" in some corporate cloud. Zim's plain-text file format offers a degree of future-proofing - as does its simple note hierarchy of files and directories. I have read comments from longtime Zim users that the program has never corrupted or lost a note, and that it has boosted their productivity. If you decide to try Zim, I hope that it will enhance your digital life. |